FZ: Last September, you launched the first issue of the Mnemoscape magazine. This magazine marks the first year of activity of Mnemoscape as a research on the aesthetics and practices of memory. Mnemoscape project was born as a blog platform. Would you return to the origins of the project, its original impulse, and contents and situations that have been activated during this first year?

EA-AF: During the planning stages of Mnemoscape, we aimed at creating a platform that would allow for collaboration and the building of a network of researchers that share our critical interest in visual culture and contemporary art dealing with issues of memory and history. However, we started from a very personal approach, that is, the territory where our individual research paths met. From this place, we branched out, interviewed practitioners and then organised a few events. The format of the project has been fast changing, in response to the different activities that we have developed both together, as Mnemoscape, and individually. The blog and the events that followed made it clear that we were interested in discussion, through face-to-face interviews and public debates. Mnemoscape Magazine is a result of these concerns: a way of collecting contributions from artists and thinkers in response to our enquiries and provocations; a space to host and feature other people's insights and thoughts. We also started a parallel activity in which we are free to experiment with different types of collaboration and a more creative way of working. As part of A Natural Oasis - a long-term research project for the biennale Mediterranea 17, which will take place in Milan in October 2015 – we are developing a practice-led body of research that will lead to a production of a work to exhibit – we can't tell you more at this point! It is very different from what we have done so far, yet very exciting. As a result, the website will also be changing very soon, first with the release of Issue#2 in March 2015 and then again in September 2015, with the publication of Issue#3. We aim at creating a platform that can mirror the transformative and collaborative nature of Mnemoscape. Perhaps it can be interpreted as a way of returning to the blog as well as to the original ethos of the project. What we can actually assert though, is that we are refusing to constrain Mnemoscape into a fixed format and that we want to take advantage of the fact that we are a web-based project.

The first Mnemoscape website used blog-based tools as Tags to outline particular issues and classify contents engaged. Several sections have been created – Monument, Re-enactment, The Archive, + Art Medium – that reflected topics explored by artists, as well as the specific mediums used to. What have risen from the research about these particular topics?

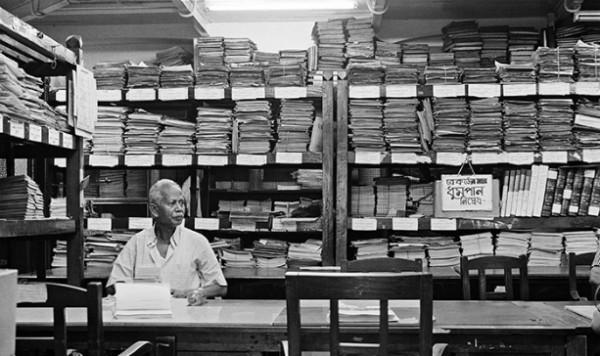

The tag system was set-up right at the planning stage, when we considered a significant amount of works that we were interested in featuring on the blog and attempted to catalogue them. At this time, we liked to think about the blog as a resource, a repository of projects concerned with issues of memory, history and 'the archival impulse', hence the strict categorization. However, the project evolved in a slightly different direction, as we quickly started to focus on face-to-face interviews and unfolding events, thus confining our work to the context in which we physically operated: London. Because of the specificity of our interests and of the artworks that we had access to, some tags are more prominent than others, such as 'the archive', or 'moving images'. Indeed, the majority of the blog content could be generally defined as being focused on exploring the ways in which artists have employed lens-based media and archival material in order to question the politics of memorialisation. Having said that, if on one hand the tag system failed (especially in providing enough examples of different practices), on the other, we still think of it as a useful tool to bring forward our research. In fact, Mnemoscape Magazine Issue#3 will be focused on monuments – a category that we neglected in our blog and that we hope to investigate more thoroughly in this publication.

By your exploration and research, you went further in the Archive subject, by a series of events and the launch of Mnemoscape publishing which first release was dedicated to the exhibition “A Tourist in Other’s People Reality” at the Vestry House Museum in London (curated by Olga Ovenden)...

All our activities between September 2013 and September 2014 have been focused on the archive. First, we produced an essay, interviews, a book and an event for the exhibition A Tourist in Other’s People Reality. Then, we organised Autobiography and the Archive, a film screening with Q&A at Whitechapel Gallery (with works by Uriel Orlow, Miranda Pennell and Sarah Pucill) and Archives for the Future, An Art and Visual Culture Conference at the University of Westminster. With these events and with the first issue of Mnemoscape Magazine, 'The Anarchival Impulse', we were interested in generating open debates that could actively challenge the role of the archive in contemporary art production, since this has often being reduced to a 'cliché'.

Archives for the Future was a particularly important point in this sense. With the conference we wanted to move away from a vision of the archive confined to the past, and, instead we aimed at projecting it into the future. To address this, we selected contributions from artists and thinkers with a wide geographical reach that, despite their diversity, allowed two main patterns to emerge: the first, was the geological metaphor while the second was the use of spatial practices both to assess actual archives and to reveal latent ones. What this reading implies, then, is that an archive for the future is embedded and de-centralised. It departs from bureaucracy and preservation, rather, it demands us to be inquisitive and become the agents of its activation. This understanding is surely part of our current research and of the next issues of the magazine.

The issue #1 of Mnemoscape magazine is devoted to the “Anarchival Impulse”. As you explain in the editorial, your purpose is to “dissect” the topic of the archive, to turn it inside out. The blog allowed you to approach different topics in a rhizomatic way, while the magazine allows you this dissection, going deeper in the features, approaching them from different points of view. In the blog you analysed the archive, while the magazine speaks about the concept of “Anarchive” as a new impulse in contemporary art, a concept forged by Hal Foster in his An Archive Impulse. The an-archive idea brings together the archive and its opposite, sometimes dismantling the (cataloguing) rules of the archive and dissolving its physical presence into the dematerialised space of the web, or transforming it into a catalogue, or a guide...

The decision to start with the “anarchival” was a sort of provocation we wanted to make against what, we feel, has turned into a fashionable and often quite sclerotic discourse around archives and memory in contemporary art. The archive has become both an aesthetic fetish and a conceptual buzz-word improperly used to refer to the most heterogeneous and eccentric types of collection. And this I think was particularly evident in the last Venice Biennial. As we have been discussing already, our research interest in the past two years has revolved mainly around archives. Yet, we have always tried to push the limits of this interpretative category, to mobilize radical readings and to criticize the omnipresent risk of regressive and nostalgic derives. So, our intent wasn't that of identifying a new trend in contemporary art, an opposite current, so to speak; rather, to be at stake was the generation of a critical discussion and a deeper understanding of a trend by way of its very challenge or, if you want, reversal.

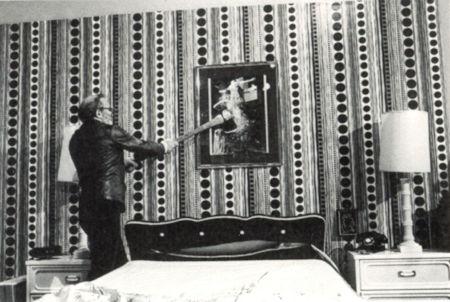

We do not see the anarchival as a counter-movement, or a new tendency at all. We see it more as a sort of subterranean double underpinning any endeavour of preservation, not just in art. In the specificity of the art sphere, this anarchival strategy may be said to be the real key issue. It is not that artists simply mine archives in search of source material or take them up as aesthetic and epistemological models. First and foremost, they overturn their power structure and experiment with alternative forms of knowledge production and display. In the magazine, the anarchival appears in many different forms: as a destructive impulse; a subversive practice; and a potential for regeneration. Flipping through the journal, you may have a sense of the semantic richness of this neologism. You can find a collection of destructive gestures and theories (Pedro Lagoa's archive of destruction) side by side with an online exhibition and growing digital archive (Tabularium curated by Alana Kushnir). The improper use of archaeological practices and terminology to engender radical protests (Az.Namusn.Art) mirrors the equally improper creation of an anomalous catalogue of Documenta 13, an object which creates interferences and glitches in the normative documentation of an art event (Alessandro Di Pietro). The iconoclastic use of water to rip and drown archival images of a fake Venezuelan modernity (Alexander Apostol) rhymes with the pathological ruptures of a project archiving the trauma of the Lebanese Civil Wars (Eirini Grigoriadou's reading of The Atlas Group).

Surely we were interested in iconoclastic gestures and we wanted to make an iconoclastic gesture of our own. But, as Bruno Latour explains beautifully, iconoclasts always end up reinforcing the object of their contestation. They are the real creators of icons.

Reading the magazine, I noticed that one feature has been analysed by different authors: the analogy. Analogy is a concept that can be used as an example of the an-archive. Indeed, normally archives follow rules like alphabetical order, keywords and classifications, etc. Warburg was one of the first to use analogy as a new and personal kind of classification, in his Atlas of Mnemosyne, as well as in his library. Books were constantly moved and rearranged to create relationships between them. Harald Szeeman did the same in his archives, arranging his documents in a system of relationships inspired by the Theatre of Memory of Giulio Camillo. New links are created by using the analogy, links that can be now easily recreated in the space of the web.

Absolutely, we think the idea of reading or using the archive differently, in a horizontal and rhizomatic way rather than vertical and arboreal one, was something we were very much interested in and that emerged in different ways in many of the contributions. This is evident for instance in Paolo Chiasera's proposal of a 2.0 art criticism where an analogical, Warburgian-inspired method is used to draw unprecedented and unexpected parallelisms, or as he calls them, synchronisms between two distant art historical moments such as 1960 minimal art and Roman painting from about 120 to 80 BC.

In the magazine, Wolfgang Ernst speaks extensively about the potential offered by the web in terms of restructuring the information according to analogy and image-based parameters, but he also reminds us of a prosaic reality where digital archives turn up to be nothing but a faithful reproduction of the alphabetical order of their analogue twins.

There is also another aspect that we would like to point out, another unconventional way of working with and through archives that is by following their “recalcitrant fragments”, fugitive or missing objects. Lucy Bayley, Ben Cranfield and Anne Massey's experiment in the ICA archives responds to this logic and suggest, as in a flicker, the emancipatory potential of an historiographical methodology freed from constrains of linear chronology and bound in material culture; a research that unfolds through a series of random encounters, unforeseen spatio-temporal connections and serendipitous constellations.

What’s next for Mnemoscape magazine?

Issue #2 will be titled In the Presence of Absence and will be launched on Monday 16th of March. In this second issue, we are focusing not on what is present, tangible and visible, but on what is absent, what was there but is not any longer, what has been removed, or attempted to be removed in a violent act of repression, what was erased, effaced, made to disappear, or what simply was not registered and thus consigned to oblivion. Within an archival discourse, we are looking on the one hand at ways of making visible blind spots and silenced/invisible subjects in existent archives; and on the other hand, we ask in which ways can the absences be archived without losing their status of absences.

In September 2015 we will publish Issue#3 which, we are happy to announce here, will be concerned with monuments, memorials and the broader notion of 'set in stone' memory, namely, relations between memorialisation and geology. With Issue#3 we are planning to launch a new structure for the magazine, with an expanded editorial board and thus a more collaborative approach. In this way, we wish to have a multitude of visions in order to broaden the reach of our research. By increasingly relying on collaboration and exchange we aim to keep on refreshing and renewing Mnemoscape.