Paola Anziché's Atlas of Thought

This text will focus on the artist book Cartaz (2012) by Italian artist Paola Anziché, published following her residency in Rio de Janeiro and her documentary Sur les traces de Lygia Clark. Souvenirs et évocations de ses années parisiennes (2011).

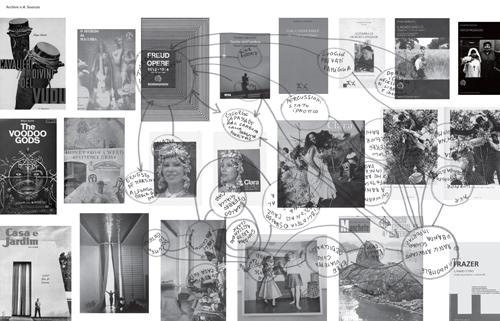

As the layout of Cartaz is designed to show the links between different phases of processing researches, the six plates composing it draw some diagrams revealing artist’s process of creation and method of research. Cartaz designs the artist’s Atlas of Thought.

To introduce Paola Anziché’s practice, we should resume it by three main issues.

1| An interactive value expressed since the description the artist give of her artworks as “to be seen with hands”. Interaction plays between the body and the piece, and it is apprehended by manipulation.

2| An experience of the space, which is transformed when the body encounters an environment by means of installation.

3| A collective dimension making the experience of the artworks more intense.

We can add to those three aspects a new one, which emerged when Paola’s researches met the work of Lygia Clark. Indeed, the practice of Brazilian artist manifested in a collective dimension always playing on the edge of a ritual, cathartic or therapeutic dimension.

Lygia Clark’s researches were loudly inspired by Freud and Lacan theories as well as by animist beliefs of her country. Lively cultural background of Brazil and artistic practices of the Sixties and Seventies reveal to be really important to apprehend Anziché’s work.

As the layout of Cartaz is designed to show the links between different phases of processing researches, the six plates composing it draw some diagrams revealing artist’s process of creation and method of research. Cartaz designs the artist’s Atlas of Thought.

To introduce Paola Anziché’s practice, we should resume it by three main issues.

1| An interactive value expressed since the description the artist give of her artworks as “to be seen with hands”. Interaction plays between the body and the piece, and it is apprehended by manipulation.

2| An experience of the space, which is transformed when the body encounters an environment by means of installation.

3| A collective dimension making the experience of the artworks more intense.

We can add to those three aspects a new one, which emerged when Paola’s researches met the work of Lygia Clark. Indeed, the practice of Brazilian artist manifested in a collective dimension always playing on the edge of a ritual, cathartic or therapeutic dimension.

Lygia Clark’s researches were loudly inspired by Freud and Lacan theories as well as by animist beliefs of her country. Lively cultural background of Brazil and artistic practices of the Sixties and Seventies reveal to be really important to apprehend Anziché’s work.

To conclude, if we examine Anziché’s practice in a more general context of actual artistic productions, we can see the changes of the artistic landscape towards a new reflection about the otherness deviating from the relational aesthetic theorized by Nicolas Bourriaud. As per Bourriaud’s words, relational aesthetic should be defined as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space”.

The question of otherness, in its cultural and social meaning, shifts today into an inner goal where the other is considered as an “other in us” – a personal, complex, system of cross-references between our biological and cultural origins and the cognitive background we develop in linking to other cultures. Many artists of today are involved in mechanisms of transmission of knowledge, of a memory where their own personal experience is grafted to experiences of other cultures. Artists of today appropriate and live cultures or situations that are distant from their original background. Their works act as a reminder of a collective memory.

This text is taken from the intervention at the round table about Lygia Clark and Paola Anziché, which followed the projection of the film Sur les traces de Lygia Clark. Souvenirs et évocations de ses années parisiennes at Museu Berardo in Lisbon in 2013.

The question of otherness, in its cultural and social meaning, shifts today into an inner goal where the other is considered as an “other in us” – a personal, complex, system of cross-references between our biological and cultural origins and the cognitive background we develop in linking to other cultures. Many artists of today are involved in mechanisms of transmission of knowledge, of a memory where their own personal experience is grafted to experiences of other cultures. Artists of today appropriate and live cultures or situations that are distant from their original background. Their works act as a reminder of a collective memory.

This text is taken from the intervention at the round table about Lygia Clark and Paola Anziché, which followed the projection of the film Sur les traces de Lygia Clark. Souvenirs et évocations de ses années parisiennes at Museu Berardo in Lisbon in 2013.

To conclude, if we examine Anziché’s practice in a more general context of actual artistic productions, we can see the changes of the artistic landscape towards a new reflection about the otherness deviating from the relational aesthetic theorized by Nicolas Bourriaud. As per Bourriaud’s words, relational aesthetic should be defined as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space”.

The question of otherness, in its cultural and social meaning, shifts today into an inner goal where the other is considered as an “other in us” – a personal, complex, system of cross-references between our biological and cultural origins and the cognitive background we develop in linking to other cultures. Many artists of today are involved in mechanisms of transmission of knowledge, of a memory where their own personal experience is grafted to experiences of other cultures. Artists of today appropriate and live cultures or situations that are distant from their original background. Their works act as a reminder of a collective memory.

The question of otherness, in its cultural and social meaning, shifts today into an inner goal where the other is considered as an “other in us” – a personal, complex, system of cross-references between our biological and cultural origins and the cognitive background we develop in linking to other cultures. Many artists of today are involved in mechanisms of transmission of knowledge, of a memory where their own personal experience is grafted to experiences of other cultures. Artists of today appropriate and live cultures or situations that are distant from their original background. Their works act as a reminder of a collective memory.

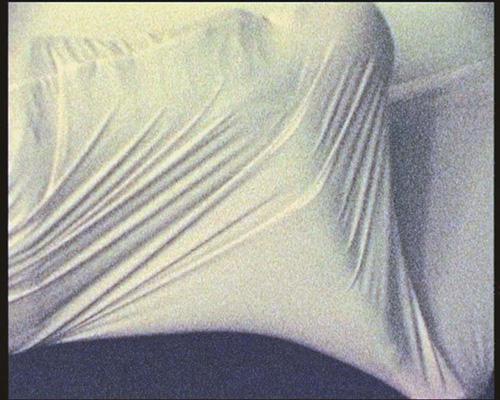

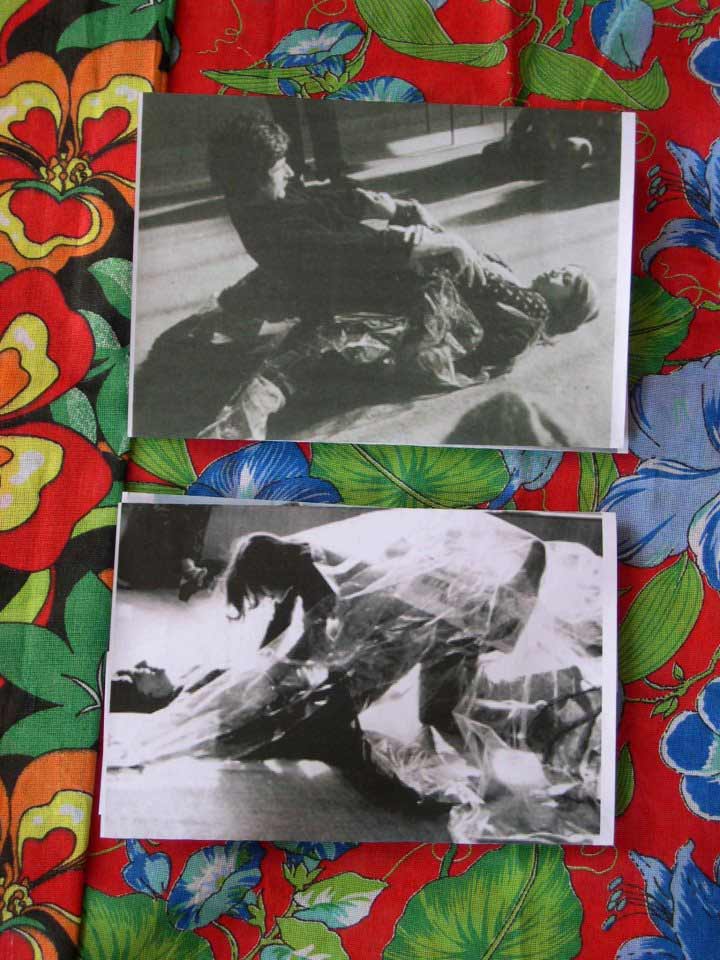

Anziché’s first contact with the work of Lygia Clark was a picture representing an action made by two persons with the help of the work Biological Architecture. A piece produced during the Sixties, Biological Architecture is made by a plastic canvas whose extremities are weaved jute bags. Lygia Clark asked some persons to place their legs inside jute bags and then try to embrace each other within the plastic canvas. What was happening during this action? Was it a performance, a play, or something else?

Such connections influenced the structure and organisation of artist-book Cartaz. When folded up, the six plates composing it superpose each other and let think to the links between them by showing titles of each plate. When unfold, the plates are independent from each other and they can be considered one by one. Plates are numbered from one to six, but the order we will follow to analyse them will reflect the one of Anziché’s researches.

This text is taken from the intervention at the round table about Lygia Clark and Paola Anziché, which followed the projection of the film Sur les traces de Lygia Clark. Souvenirs et évocations de ses années parisiennes at Museu Berardo in Lisbon in 2013.

www.paolanziche.net

www

www.paolanziche.net

www

Cartaz plates should be read and analysed in a multiplicity of different ways, according to one’s interests and relationship with the artist. This text is only one way to read Paola Anziché’s work and to draw connections in between her works and her interests towards cultures full of tradition and meanings.

From these questions took its origins Sur les traces de Lygia Clark. Souvenirs et évocations de ses années parisiennes documentary. The film focuses on the Parisian period of Lygia Clark’s lessons at La Sorbonne (Faculty of Plastic Arts and Sciences of Art also known as Saint-Charles). Actually, it is really hard to find documentation about this specific period of Clark’s work: the artist was more experimenting collective situations with her students than she produced artworks. As per the ephemeral nature of these situations happening during the courses, only few photographs exist to document them. Thus, the film tries to reconstitute them as he draws Clark’s character by giving voice to these persons who were collaborating with her at that time; scenes of situations re-enacted are shown to give rhythm to interviews with ancient students or collaborators.

Trying to fill this lack of documentation, Paola Anziché has collected documentation related to this encounters. More, this archive shows how, during the period of researches for the film, Lygia Clark and her work became an obsession and collecting objects and documents recalling her, a fetishist attitude. But when presented with the film, objects and documentation become clues allowing everyone to reconstruct its own experience of the work of Lygia Clark. When displayed, they act less as an archive than an atlas (we refer to the atlas as elaborate by Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne): a network of significant elements making sense in their mutual relationship.

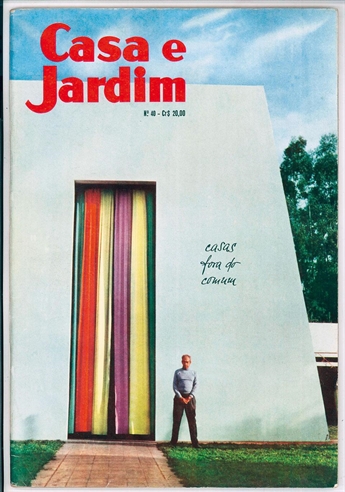

Elements of the archive (a text by Yves Alain Bois, a picture of Suely Rolnik or Alexandra Clark, copies of magazines of the Sixties, catalogues, notes on post-it, etc.) allow the artist to weave a symbolic architecture around the figure of Lygia Clark, her historical and artistic context and reflect connection with people who knew her, and Anziché met. Traces of Lygia Clark are important in the archive as well as in the film.

Elements of the archive (a text by Yves Alain Bois, a picture of Suely Rolnik or Alexandra Clark, copies of magazines of the Sixties, catalogues, notes on post-it, etc.) allow the artist to weave a symbolic architecture around the figure of Lygia Clark, her historical and artistic context and reflect connection with people who knew her, and Anziché met. Traces of Lygia Clark are important in the archive as well as in the film.

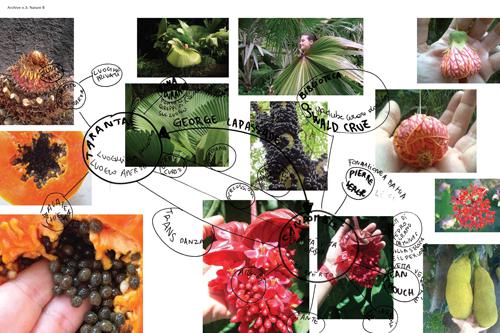

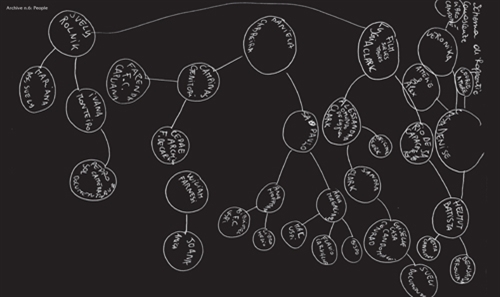

Archive n. 6: People draws a “diagram of relationships and connections” throughout Brazil: from the members of Clark’s family working on the artist archive or psychoanalyst Suely Rolnik who collects interviews with people who met the Brazilian artist, to people connected with some other important Brazilian figures, such as architect Flavio de Carvalho or artist Hélio Oticica.

Related to the names is also a geographical itinerary which moves from Rio de Janeiro to Sao Paulo and the routes that follow traces of Tropicália movement. Carvalho’s researches on experiencing the architectural space and Oiticica’s collective performances have definitely nourished Anziché’s work.

Related to the names is also a geographical itinerary which moves from Rio de Janeiro to Sao Paulo and the routes that follow traces of Tropicália movement. Carvalho’s researches on experiencing the architectural space and Oiticica’s collective performances have definitely nourished Anziché’s work.

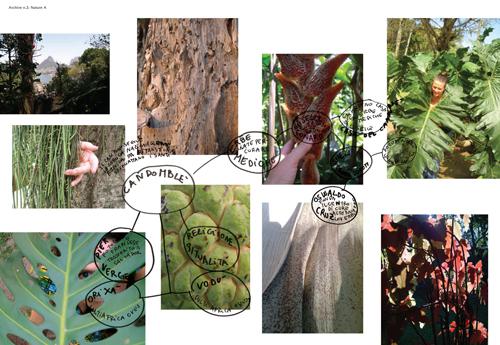

Her researches in Brazil have also been strongly influenced by the candomblé parties, and especially the one organised once a year in homage to the popular Brazilian singer Clara Nunes. All the 1st of November, a group of Candomblé musicians meet in the São João Batista cemetery in Rio de Janeiro, they adorn the singer’s grave with yellow and white flowers and sing her songs. Paola Anziché took part in the ritual, and she relayed it in the video A Clara (2012), focusing her attention on those details – movement of the hands, clothes, objects, etc. – that are of great importance for the rite and its cathartic dimension.

All the significant objects collected by Paola Anziché all along her stay in Brazil are presented in the plate Archive n.1: Objects. From these objects the story of Brazilian nation draws up, as well as its cultural traditions, its landscape and nature. The plate traces a symbolic map where nature – little stones, berries, a bark – meet people – notes, professional cards –, economics – money –, and cultural and artistic context – a magazine about Flavio de Carvalho, a floral fabric. By these objects, we can imagine the steps of her trip and of her encounters in Brazil.

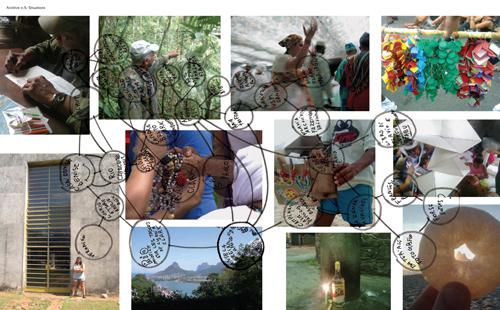

Archive n. 5: Situations combines the “diagram of relationships and connections” of plate six with photographs. Persons met in Brazil are here contextualised by the help of the images on the background. Images telling about a Brazil of people and rites, of nature and music, of religion and culture, where Paola’s wanderings are grafted.

During her stay, Anziché has visited some tropical gardens such as Rio de Janeiro Tijuca forest, Burle Marx Jardin and Jardin Botanico. Vegetal species shown in these gardens are of a great importance in the plate Archive n. 2: Nature A. Powerfulness of nature relies here with a religious and spiritual attitude linking together candomblé animist rituals and natural medicine.

Inspired by natural medicine, once back in Italy Paola Anziché created I Maggi (2012), a series of sculptures suggesting the ancient habits of an archaic and rural world that celebrated the spring by adorning the branches with coloured ribbons. Here the ribbons are made with madras, fabrics that have a particular meaning as they were used by Creole women since European colonization.

Madras have also been used to create Choreographica Madras (2010), a curtain made by vertical strips of fabric of about 15 or 20 cm wide. This work inserts into the exhibition space by creating a joyful redundancy to the architecture, playing with the space.

We can recognize here the same interest in space and colour than in Flavio de Carvalho’s architectures. It will be developed further by painting coloured strips upon the store windows of the Gallery of Modern Art in Turin (exhibition Vitrine 270°, 2012); touches of colour change the experience of the exhibition space.

Links between architectures and tropical botanical species are revealed in the plate Archive n.3: Nature B. A photograph shows the artist wearing a huge leaf; its architectural structure can be re-imagined as if it was a shelter, a personal home, a garment, a roof.

“Roofs to be worn”: this is Anziché’s description of the series of sculptures Yurte (2011). Similarly to tropical leafs, these sculptures are personal architectures, objects that spectators can wear. Made by jute coffee bags, Yurte refer to nomadic tents, but they are also homage to a manual savoir-faire.

Magic world is brought together in Archive n. 4: Sources. Here, the writings of Freud – remind how psychoanalysis was really important for Lygia Clark – are associated to books about ritual traditions, to ethnological and anthropological studies, to the singer Clara Nunes and her link to candomblé.