Instead of seeing Bertken’s life and writing as a transparent window [6] through which to search for the authentic experience of an anchoress in medieval Utrecht, I have sought to begin a dialogue with her story, and by knotting the knowledge that emerges from that conversation into my own experience begin to see how it can be made relevant for today [7]. This knotting together is for me the joy of being an artist, and once you have read this you will find a short text I wrote myself, to record, in my own way, the different rooms and conditions in which I wrote this paper.

I have found it difficult to talk to others about my fascination with Suster Bertken. Do I secretly want to be a Nun, or a hermit? People ask me. No is the answer. But I do stake a claim for the importance of an autonomous interior life, a private wilderness where the imagination can roam unselfconsciously and without restraint; and for a small space in the outside world where this imagining can happen.

This paper is just one part of a much wider project, for which there is not enough time to discuss today. I would love to tell you more about Etty Hillesum, for example, and how her important story could be made to converse with Bertken’s. But that will have to wait for another time. So instead I will end this paper with Etty’s words:

“These five minutes have been mine. Behind me the clock ticks away. The sounds in the house and on the street are like distant surf. […] Here, beside this great black surface that is my desk, I feel as though I am on a desert island. […] And what does it matter whether I study one page more or less of a book? If only I listened to my own rhythm, and tried to live in accordance with it.” (Hillesum, E, 1943, p.89)

I have found it difficult to talk to others about my fascination with Suster Bertken. Do I secretly want to be a Nun, or a hermit? People ask me. No is the answer. But I do stake a claim for the importance of an autonomous interior life, a private wilderness where the imagination can roam unselfconsciously and without restraint; and for a small space in the outside world where this imagining can happen.

This paper is just one part of a much wider project, for which there is not enough time to discuss today. I would love to tell you more about Etty Hillesum, for example, and how her important story could be made to converse with Bertken’s. But that will have to wait for another time. So instead I will end this paper with Etty’s words:

“These five minutes have been mine. Behind me the clock ticks away. The sounds in the house and on the street are like distant surf. […] Here, beside this great black surface that is my desk, I feel as though I am on a desert island. […] And what does it matter whether I study one page more or less of a book? If only I listened to my own rhythm, and tried to live in accordance with it.” (Hillesum, E, 1943, p.89)

[6] Walton, H (2007). Imagining Theology: Women, Writing and God. T & T Clark, p. 24

[7] ibid, p. 12

From Within and Without:

the Dutch Anchorite Suster Bertken, 1426/7 - 1514

In the high Middle Ages, women began to take a more prominent role in theological writings. As a writer Bertken was part of the Europe-wide devotio moderna movement, “a movement shaped and united by texts” (Simon, A, 2013, p. 232). Bertken was in the privileged position of being very well educated, and as an anchoress would have had access to a wide range of literature. In fact, reading was positively encouraged.

However Bertken acted inside a contradictory belief system. Considered weak and prone to heresy, women were thought to need strict guidance. At the same time, the prayers of women were thought to be more efficacious than those of men [4] . For this reason convents were often placed near the city walls, as communities of women were seen as bulwarks against evil entering the city.

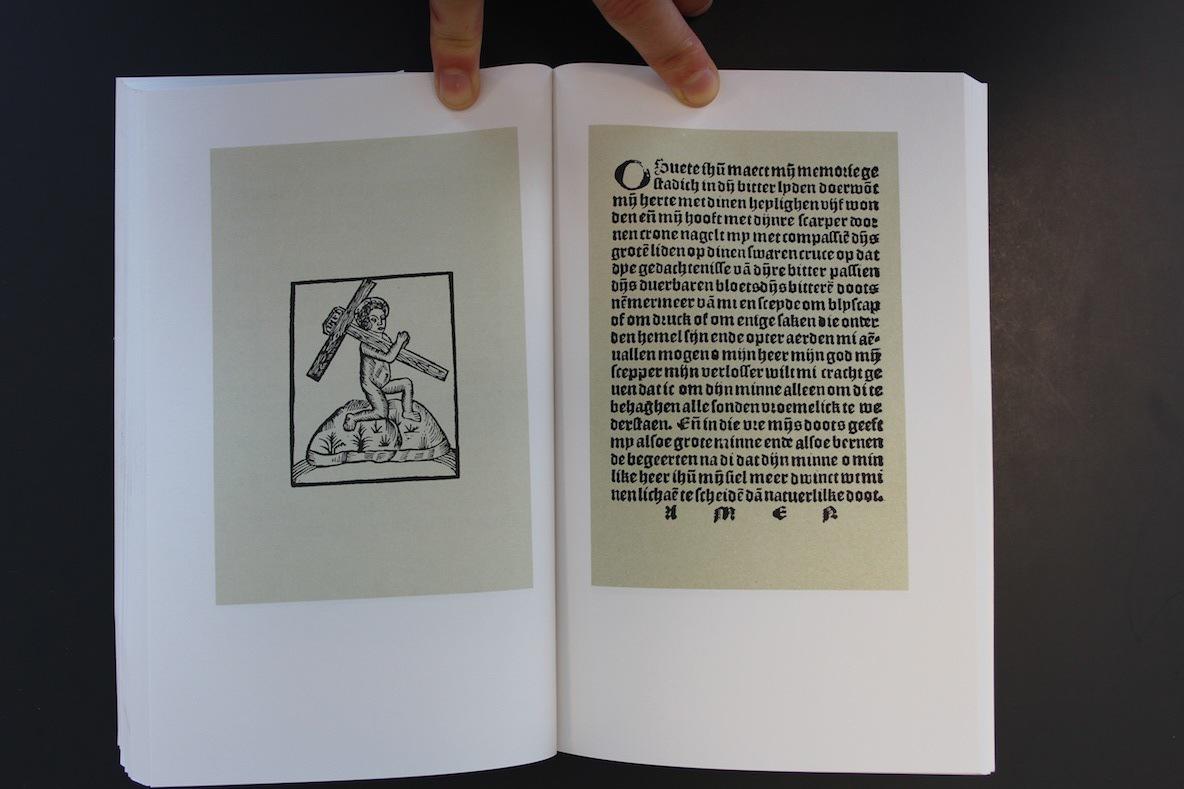

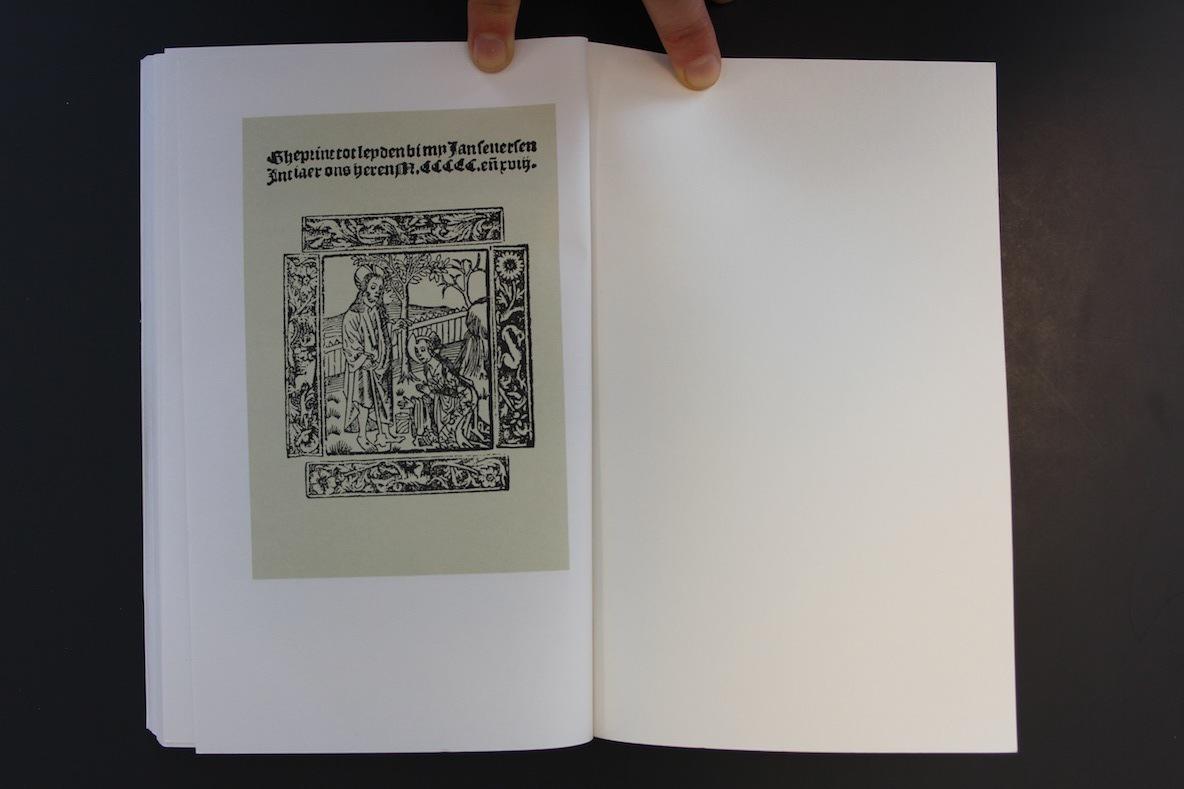

What remains today of Berkten’s writing are two small volumes of prose and nine poems, printed shortly after her death by three different publishers, making her the first Dutch woman to be published.

These texts cover a range of spiritual themes, and testify that in keeping with the anchoritic tradition Bertken focused intense meditation on the life of Christ, and through this attempted to achieve a subjective appropriation of his pain and redemptive act.

I think it is important to note here that Bertken’s sexuality would have been dealt with very differently to the men of religious orders. According to archaeologist Roberta Gilchrist, the celibacy demanded of monks and priests “created a public space within the body; [they] became accessible to others through the creation of public space where personal sexuality had previously resided”. It was not thought that women could achieve this asexual state, and so “their bodies become private spaces […] nuns committed their virginity to the church as ‘Brides of Christ’. Nuns gave up possession of their own bodies; equally, they became private spaces inaccessible to others” (Gilchrist, R, 1997) . In the mystical tradition this private sensuality was retained, and what was considered a universal female desire – that for a husband, a lover – was transformed and re-directed towards Christ, the symbolic bridegroom.

[4} Dickens, A J (2009). The Female Mystic – Great Women Thinkers of the Middle Ages. I B Tauris & Co Ltd, p. 3

However Bertken acted inside a contradictory belief system. Considered weak and prone to heresy, women were thought to need strict guidance. At the same time, the prayers of women were thought to be more efficacious than those of men [4] . For this reason convents were often placed near the city walls, as communities of women were seen as bulwarks against evil entering the city.

What remains today of Berkten’s writing are two small volumes of prose and nine poems, printed shortly after her death by three different publishers, making her the first Dutch woman to be published.

These texts cover a range of spiritual themes, and testify that in keeping with the anchoritic tradition Bertken focused intense meditation on the life of Christ, and through this attempted to achieve a subjective appropriation of his pain and redemptive act.

I think it is important to note here that Bertken’s sexuality would have been dealt with very differently to the men of religious orders. According to archaeologist Roberta Gilchrist, the celibacy demanded of monks and priests “created a public space within the body; [they] became accessible to others through the creation of public space where personal sexuality had previously resided”. It was not thought that women could achieve this asexual state, and so “their bodies become private spaces […] nuns committed their virginity to the church as ‘Brides of Christ’. Nuns gave up possession of their own bodies; equally, they became private spaces inaccessible to others” (Gilchrist, R, 1997) . In the mystical tradition this private sensuality was retained, and what was considered a universal female desire – that for a husband, a lover – was transformed and re-directed towards Christ, the symbolic bridegroom.

[4} Dickens, A J (2009). The Female Mystic – Great Women Thinkers of the Middle Ages. I B Tauris & Co Ltd, p. 3

And so Bertken’s writing deals with the birth and death of Christ, and the problems of trying to die in the world and live only for him. They deal with her relation to Christ as bridegroom, and her longing to be united with him [5].

Contemporary scholars who have studied Bertken’s writing have observed that these are not the writings of a simple recluse, created in innocent isolation. Rather they draw upon a long literary, intellectual, theological and mystical tradition. This mystical tradition was one way in which Bertken as a woman could gain power. A mystic can claim that a divine authority has demanded that they speak through their writing, and mystical commission trumps earthly, male, authority.

You will have found close by extracts from two English translations of her poems, highly coded texts that weave metaphors of the enclosed garden and Christ as gardener and lover, the different roles that women could aspire to, and a re-stating of her retreat from the world.

[5] Nieuwenhove, RV; Faesen, R; Rolfson, H. (eds.), (2008) Late Medieval Mysticism of the Low Countries. USA: Paulist Press, p. 204

Contemporary scholars who have studied Bertken’s writing have observed that these are not the writings of a simple recluse, created in innocent isolation. Rather they draw upon a long literary, intellectual, theological and mystical tradition. This mystical tradition was one way in which Bertken as a woman could gain power. A mystic can claim that a divine authority has demanded that they speak through their writing, and mystical commission trumps earthly, male, authority.

You will have found close by extracts from two English translations of her poems, highly coded texts that weave metaphors of the enclosed garden and Christ as gardener and lover, the different roles that women could aspire to, and a re-stating of her retreat from the world.

[5] Nieuwenhove, RV; Faesen, R; Rolfson, H. (eds.), (2008) Late Medieval Mysticism of the Low Countries. USA: Paulist Press, p. 204

Joanna Peace (b. 1982, UK) is an artist and writer based in Glasgow. She uses writing, object-making, video and sound to embody the shifting encounter between self and environment; examining the agency that space – physically and socially constructed, tangible and imaginary - has to shape the experiences of women, and the ways women, as both the subject and author of their lives, push back against this shaping.

Joanna’s current research centres around the question how can a poetic embodiment of the related positions ‘hermit’ and ‘collaborator’ further an understanding of the conditions necessary for critical and creative thought and production? This has emerged from an increasing consciousness of the challenging conditions in which creative work is undertaken today, and a growing interest in the history of lives lived to a singular rhythm.

Joanna has worked and exhibited internationally. After many years in London Joanna upped sticks in 2012 and moved north to undertake an AHRC-funded Masters at the Glasgow School of Art. Her most recent projects include HOUSE VISIT, which commenced in May 2014 with a residency in The Hague funded by the a-n New Collaborations Bursary; a paper on the medieval hermit Suster Bertken delivered at the interdisciplinary symposium ‘Buildings & the Body’ at Southampton University in June 2014; and a video and sculptural installation included in ‘?!*’, a festival celebrating the written and spoken word held at The Pipe Factory, Glasgow, also in June 2014.

Joanna is a visiting tutor at the Glasgow School of Art and has delivered workshops for the Glasgow Sculpture Studios and Depot Arts. She was co-editor of Undercurrents Magazine between 2012 and 2014. While in London Joanna worked for a number of public institutions including The Photographers’ Gallery.

http://joanna-peace.squarespace.com/

Joanna’s current research centres around the question how can a poetic embodiment of the related positions ‘hermit’ and ‘collaborator’ further an understanding of the conditions necessary for critical and creative thought and production? This has emerged from an increasing consciousness of the challenging conditions in which creative work is undertaken today, and a growing interest in the history of lives lived to a singular rhythm.

Joanna has worked and exhibited internationally. After many years in London Joanna upped sticks in 2012 and moved north to undertake an AHRC-funded Masters at the Glasgow School of Art. Her most recent projects include HOUSE VISIT, which commenced in May 2014 with a residency in The Hague funded by the a-n New Collaborations Bursary; a paper on the medieval hermit Suster Bertken delivered at the interdisciplinary symposium ‘Buildings & the Body’ at Southampton University in June 2014; and a video and sculptural installation included in ‘?!*’, a festival celebrating the written and spoken word held at The Pipe Factory, Glasgow, also in June 2014.

Joanna is a visiting tutor at the Glasgow School of Art and has delivered workshops for the Glasgow Sculpture Studios and Depot Arts. She was co-editor of Undercurrents Magazine between 2012 and 2014. While in London Joanna worked for a number of public institutions including The Photographers’ Gallery.

http://joanna-peace.squarespace.com/

Further sources:

Aelst, J V (2014) Requiescat in pace: De 500e sterfdag van Suster Bertken. In: Tijdschrift Oud Utrecht

Agrest, Diane. Architecture from Without: Body, Logic & Sex (1993)

Anderson, E; Lahnemann, H; Simon, A (eds) (2013). A Companion to Mysticism and Devotion in Northern Germany in the Late Middle Ages. Brill Press

Barthes, R. How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces. Columbia Press

Conference on Feminist Writing, Centre for Feminist Research Goldsmiths, London, June 2014

Gilchrist, R (1997). Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women. Routledge

Gilchrist, R (2005). Women’s Space: Patronage, Place and Gender in the Medieval Church. USA: State University of New York

Ghirardo, D. Women and Space in a Renaissance Italian City. In: Borden, I; Rendell, J (eds.) Intersections: Architectural Histories and Critical Theories. Psychology Press

Groning, P (dir.) Into Great Silence, 2005

An Interrupted Life: The Diaries and Letters of Etty Hillesum 1941 – 43. Persephone Books

hooks, b (1989). Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness. In: Rendell, J (ed)

Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Routledge

Latimer, Q (2014). Interiors: some stanzas on the pleasures of privacy [Recorded talk]. Available at: http://www.chisenhale.org.uk/media/media.php?id=57 [Accessed June 2014]

Pearson, L (ed.) It Is Almost That: A Collection of image + Text Work by Women Artists & Writers. Siglio

Perkins Gilman, C (1892). The Yellow Wallpaper

Rendell, J (2014). Site-Writing [talk] Glasgow School of Art

Rendell, J (2003). To miss the desert. In: Wade, G (ed.) Nathan Coley: Black Tent.

Robertson, E. An Anchorhold of Her Own: Female Anchoritic Literature in Thirteenth-Century England [online pdf]. Available at: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/An-Anchorhold-of-Her-Own.pdf [Accessed April 2014]

Vynckier, H. Poetry From Behind Bars: Some Translations from the Dutch Recluse Suster Bertken (1427 – 1514). In Mystics Quarterly

Wilson-Goldie, K. Seeing and Believing – the spiritual and the secular in art today. Frieze no. 161 March 2014

Zuidam, R (2010). On Language and Musical Composition [online article]. Available at: http://www.robertzuidam.com/essaysErasmusLectures%20III.htm [Accessed April 2014]

Aelst, J V (2014) Requiescat in pace: De 500e sterfdag van Suster Bertken. In: Tijdschrift Oud Utrecht

Agrest, Diane. Architecture from Without: Body, Logic & Sex (1993)

Anderson, E; Lahnemann, H; Simon, A (eds) (2013). A Companion to Mysticism and Devotion in Northern Germany in the Late Middle Ages. Brill Press

Barthes, R. How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces. Columbia Press

Conference on Feminist Writing, Centre for Feminist Research Goldsmiths, London, June 2014

Gilchrist, R (1997). Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women. Routledge

Gilchrist, R (2005). Women’s Space: Patronage, Place and Gender in the Medieval Church. USA: State University of New York

Ghirardo, D. Women and Space in a Renaissance Italian City. In: Borden, I; Rendell, J (eds.) Intersections: Architectural Histories and Critical Theories. Psychology Press

Groning, P (dir.) Into Great Silence, 2005

An Interrupted Life: The Diaries and Letters of Etty Hillesum 1941 – 43. Persephone Books

hooks, b (1989). Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness. In: Rendell, J (ed)

Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. Routledge

Latimer, Q (2014). Interiors: some stanzas on the pleasures of privacy [Recorded talk]. Available at: http://www.chisenhale.org.uk/media/media.php?id=57 [Accessed June 2014]

Pearson, L (ed.) It Is Almost That: A Collection of image + Text Work by Women Artists & Writers. Siglio

Perkins Gilman, C (1892). The Yellow Wallpaper

Rendell, J (2014). Site-Writing [talk] Glasgow School of Art

Rendell, J (2003). To miss the desert. In: Wade, G (ed.) Nathan Coley: Black Tent.

Robertson, E. An Anchorhold of Her Own: Female Anchoritic Literature in Thirteenth-Century England [online pdf]. Available at: http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/An-Anchorhold-of-Her-Own.pdf [Accessed April 2014]

Vynckier, H. Poetry From Behind Bars: Some Translations from the Dutch Recluse Suster Bertken (1427 – 1514). In Mystics Quarterly

Wilson-Goldie, K. Seeing and Believing – the spiritual and the secular in art today. Frieze no. 161 March 2014

Zuidam, R (2010). On Language and Musical Composition [online article]. Available at: http://www.robertzuidam.com/essaysErasmusLectures%20III.htm [Accessed April 2014]

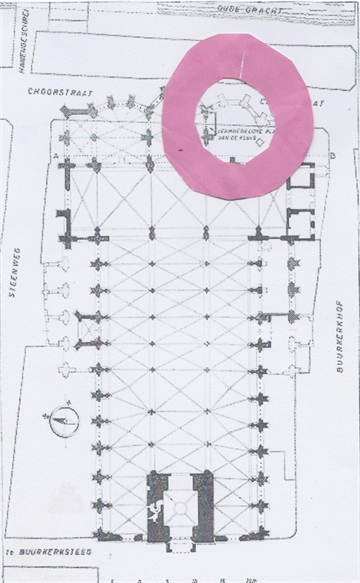

You can see from this floor plan that her cell was built inside the walls, though remaining on the margins: engulfed by the larger architectural structure as it remains separate from it.

How women positioned themselves within religious and civic space, or were themselves positioned, offers historians a great deal of information on the social dynamics of a community. Many of the texts I have read for this paper draw upon the work of French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu. His writings on the ways in which our built environment represents and enacts the laws of the community, as well as the deeper structures of that community’s psyche, have been used widely by feminists, and have been helpful in my thinking for this paper [1].

In the Medieval period, women were often deemed polluted and dangerous and so restricted from accessing sacred spaces. Bertken, however, as a virgin devoted to God, would have been thought of as too fragile to be allowed into social spaces where she might be contaminated by others, and so in need of seclusion and protection [2].

With these beliefs made manifest in the architecture of Utrecht, Bertken’s body was placed inside the body of the church, which was itself inside the body of the wider city, each component slotting together as neatly as a Russian doll.

How women positioned themselves within religious and civic space, or were themselves positioned, offers historians a great deal of information on the social dynamics of a community. Many of the texts I have read for this paper draw upon the work of French anthropologist Pierre Bourdieu. His writings on the ways in which our built environment represents and enacts the laws of the community, as well as the deeper structures of that community’s psyche, have been used widely by feminists, and have been helpful in my thinking for this paper [1].

In the Medieval period, women were often deemed polluted and dangerous and so restricted from accessing sacred spaces. Bertken, however, as a virgin devoted to God, would have been thought of as too fragile to be allowed into social spaces where she might be contaminated by others, and so in need of seclusion and protection [2].

With these beliefs made manifest in the architecture of Utrecht, Bertken’s body was placed inside the body of the church, which was itself inside the body of the wider city, each component slotting together as neatly as a Russian doll.

[1] Texts which draw upon Bourdieu’s writings include Women and Space in a Renaissance Italian City by Diane Ghirardo and Women’s Space: Patronage, Place and Gender in the Medieval Church by Roberta Gilchrist

[2] Gilchrist, R (2005). Women’s Space: Patronage, Place and Gender in the Medieval Church. USA: State University of New York, p.2

So both sight and speech were to be feared. But what of hearing? In the Medieval period hearing was considered more important than sight, and it was not until the Renaissance that this hierarchy was reversed. If we take that earlier idea, that the body of the anchoress and the building that contains it can be collapsed into one another, then perhaps we can think of those two small windows as Bertken’s own ears.

Two very different sonic landscapes would have reached those ears. From the church, the regular cycles of prayer and song. From the street the chaotic and irregular sounds of chatter and trading, of animals and carts. I like to imagine these clashing rhythms, sacred and profane, flowing in and out of Bertken’s cell, mingling with the rhythm of her own breath and heartbeat.

Another word that Roland Barthes examines in his lectures ‘How to Live Together’ is rhuthmos. Rhuthmos, according to Barthes, is a distinctive, improvised and changeable form, by definition individual. This fluid form can be acted upon by disruptive or controlling power: disrhythmy or heterorhythmy (Barthes, R, 1976 – 1977, p.9).

The sounds and rhythms of her environment would have affected not just Bertken’s behaviour, for example through her following of the daily cycle of prayer, but I would suggest also affected her thoughts and writing.

Two very different sonic landscapes would have reached those ears. From the church, the regular cycles of prayer and song. From the street the chaotic and irregular sounds of chatter and trading, of animals and carts. I like to imagine these clashing rhythms, sacred and profane, flowing in and out of Bertken’s cell, mingling with the rhythm of her own breath and heartbeat.

Another word that Roland Barthes examines in his lectures ‘How to Live Together’ is rhuthmos. Rhuthmos, according to Barthes, is a distinctive, improvised and changeable form, by definition individual. This fluid form can be acted upon by disruptive or controlling power: disrhythmy or heterorhythmy (Barthes, R, 1976 – 1977, p.9).

The sounds and rhythms of her environment would have affected not just Bertken’s behaviour, for example through her following of the daily cycle of prayer, but I would suggest also affected her thoughts and writing.

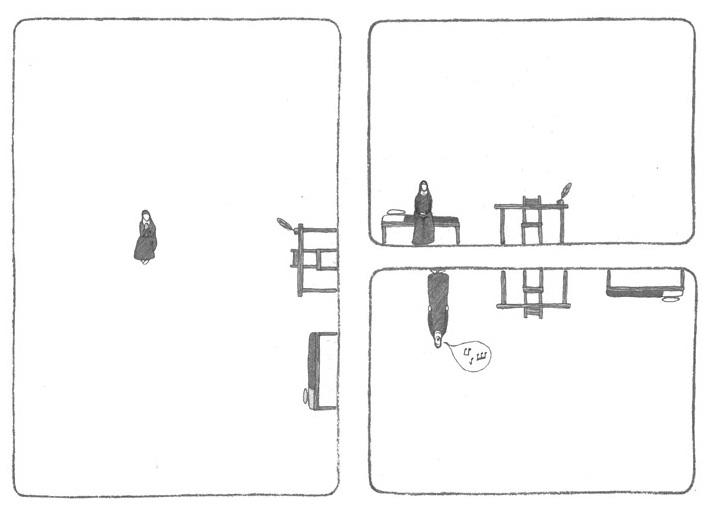

The comic and its protagonist stayed in my mind long after I first saw it. And so I struck up an email conversation with Maartje, in an attempt to pick apart what it was about Bertken’s life and work that fascinated us both, as committed feminists with no religious belief.

This paper has expanded out of that picking apart, and deals with the particular conditions in which Suster Bertken lived and worked, with both the real and imagined space she found for thought and production.

We will work our way steadily from outside to inside, from the act Suster Bertken undertook in becoming an anchorite, to the work she created in her cell, and finally into the central and unknowable figure of Bertken herself, onto which I am able to project something of myself.

This paper has expanded out of that picking apart, and deals with the particular conditions in which Suster Bertken lived and worked, with both the real and imagined space she found for thought and production.

We will work our way steadily from outside to inside, from the act Suster Bertken undertook in becoming an anchorite, to the work she created in her cell, and finally into the central and unknowable figure of Bertken herself, onto which I am able to project something of myself.

Reading these texts, I am drawn to their insistent and passionate tone, both directly emotional and intelligent. To my amateur ears they sound like someone distinct, rather than just a mouthpiece for the dogma of the time.

Bertken had many regulations imposed on both her body and mind. But having chosen to become an anchorite, to read and reflect, listen and write for 57 years, the lonely wilderness of her enclosure would have filled with a thousand words, offering Bertken a more solid refuge than any stone wall.

Bertken had many regulations imposed on both her body and mind. But having chosen to become an anchorite, to read and reflect, listen and write for 57 years, the lonely wilderness of her enclosure would have filled with a thousand words, offering Bertken a more solid refuge than any stone wall.

While writing this paper Bertken herself has remained elusive, a stubborn enigma. This photograph is of a small section of the only other physical trace of Bertken in Utrecht – a stone laid into the pavement on the spot where her cell once stood. Carved into the stone is the floorplan of the Buurkerk as it was in Bertken’s time, with the shape of her anchorhold picked out in metal.

It is not just the lack of physical evidence that makes Bertken elusive. As Margaret Atwood so eloquently put it in ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’:

“We may call Eurydice forth from the world of the dead, but we cannot make her answer; and when we turn to look at her we glimpse her only for a moment, before she slips from our grasp and flees. As all historians know, the past is a great darkness, and filled with echoes. Voices may reach us from it; but what they say to us is imbued with the obscurity of the matrix out of which they come; and try as we may, we cannot always decipher them precisely in the clearer light of our own day.” (Atwood, M, 1985, p. 324)

It is not just the lack of physical evidence that makes Bertken elusive. As Margaret Atwood so eloquently put it in ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’:

“We may call Eurydice forth from the world of the dead, but we cannot make her answer; and when we turn to look at her we glimpse her only for a moment, before she slips from our grasp and flees. As all historians know, the past is a great darkness, and filled with echoes. Voices may reach us from it; but what they say to us is imbued with the obscurity of the matrix out of which they come; and try as we may, we cannot always decipher them precisely in the clearer light of our own day.” (Atwood, M, 1985, p. 324)

“There is a strange little melody inside me that sometimes cries out for words. But through inhibition, lack of self-confidence, laziness, and goodness knows what else, that tune remains stifled, haunting me from within […] Sometimes I want to flee with everything I possess into a few words, seek refuge in them. But there are still no words to shelter me. That is the real problem. I am in search of a haven, yet I must first build it for myself, stone by stone. Everyone seeks a home, a refuge. I am always in search of a few words.“

(Hillesum, E, 1942, p.67)

(Hillesum, E, 1942, p.67)

Before this mortal death, Bertken underwent the symbolic death required of an anchorite. On the day of her enclosure, a requiem mass was said. Following the service and with those present singing the liturgy of burial, Bertken was led to her cell. Stepping barefoot into the anchorhold the Bishop said ‘Rest in Peace’, and Bertken was locked in. Departing one world she entered another.

As I read aloud this extract from the diary of Dutch writer Etty Hillesum, from the 1940s, its poetic conflation of melody and word, word and refuge reverberates through me, bodily. As an artist and writer myself, I have found refuge in many rooms, enclaves of thought and production each with their own particular qualities of light and space, sound and temperature. Each with their own set of social rules and forms of interaction. These conditions, shaping me, have shaped my work.

Much of my practice as an artist seeks to examine and animate the contours of socially, culturally and emotionally loaded space and its affect on individual women, women both known to me and constructed from historical research. It was a similar act by comic artist and good friend of mine Maartje Schalkx that first led me to the Dutch anchorite, mystic and writer Suster Bertken.

Maartje was born and brought up in Utrecht, Bertken’s birthplace, and growing up her Mum would regularly point out a large stone in a busy shopping street that commemorates Bertken. “At first I thought there was something very romantic about her, [Maartje once told me] to lock yourself up to live a life of religious contemplation; a bride of Jesus. That kind of devotion was very appealing even to an atheist like myself. It was only later that I started to think of it as something more radical, but also pragmatic.”

Much of my practice as an artist seeks to examine and animate the contours of socially, culturally and emotionally loaded space and its affect on individual women, women both known to me and constructed from historical research. It was a similar act by comic artist and good friend of mine Maartje Schalkx that first led me to the Dutch anchorite, mystic and writer Suster Bertken.

Maartje was born and brought up in Utrecht, Bertken’s birthplace, and growing up her Mum would regularly point out a large stone in a busy shopping street that commemorates Bertken. “At first I thought there was something very romantic about her, [Maartje once told me] to lock yourself up to live a life of religious contemplation; a bride of Jesus. That kind of devotion was very appealing even to an atheist like myself. It was only later that I started to think of it as something more radical, but also pragmatic.”

Stone memorial to Suster Bertken in Utrecht. Found internet image

Installation of the video The Chant Went On and On (as he walked along that hot day), 2014

1. Sound, text and sculptural installation. Part of Idiorrhthmy at Billytown, The Hague, May 2014

Suster Bertken, born in Utrecht, The Netherlands, in 1426/7, was 30 when she made the decision to become an anchorite and give her life over to God. With permission from the Bishop, she had a cell built at her own expense in the south-facing wall of the Buurkerk, the most important parish church in Medieval Utrecht. There she was enclosed for fifty-seven years, composing poetry and songs, praying, reading and meditating, and giving counsel to passers by in return for food.

From contemporary documents we gather that she wore a hair shirt on her naked skin with a simple grey dress over it, and that she went barefoot. She never burnt a fire in her cell, and never ate meat or dairy. Though the anchoritic life was not uncommon at that time, and a number of churches had anchorholds attached to them, this asceticism was more extreme than most. It is this dedication, plus her significant writing output, which made Bertken a well-known figure of her day. Upon her death in 1514 at the age of 87, they buried her under her cell in keeping with her wishes.

From contemporary documents we gather that she wore a hair shirt on her naked skin with a simple grey dress over it, and that she went barefoot. She never burnt a fire in her cell, and never ate meat or dairy. Though the anchoritic life was not uncommon at that time, and a number of churches had anchorholds attached to them, this asceticism was more extreme than most. It is this dedication, plus her significant writing output, which made Bertken a well-known figure of her day. Upon her death in 1514 at the age of 87, they buried her under her cell in keeping with her wishes.

Photograph of extract from a facsimiles book of Suster Bertken’s writings. Courtesy The Utrecht Archives

Now I want to take you inside Bertken’s cell or anchorhold as it’s called. There would have been a pot, a cup and a plate. A writing tool, a Bible, a crucifix. A chair and a table. There is no record of a bed in Bertken’s cell, so she may have used a straw mattress.

In writings from that period, the anchorite’s body is both imagined and described as synonymous with the anchorhold itself, “an overlap that used spatial language not only to describe the female recluse but also to control her bodily actions” (Gilchrist, R, 2005, p. 10). As this suggests, there were strict rules governing all aspects of Bertken’s life in her cell, from her daily routine to the focus of her thoughts. Many of these rules can be found in the Ancrene Wisse, a thirteenth century guide for anchorites.

One of the purposes of this guide, which was primarily directed at female anchorites, was to teach her how to ‘protect her heart’ [3].

Like all anchorholds of the time, Bertken’s cell would have contained two small windows, one facing onto the street, and one facing into the church, through which she could participate in ecclesiastical services. Though functional, the Ancrene Wisse stresses that these windows were to be feared, as both seeing and being seen contained great potential for evil: “My dear sisters, love your windows as little as you can”. For from sight comes “all the misery that there now is and ever yet was and ever shall be…” (Hermitary,.com, 2003).

Speech was also discouraged, as worldly gossip could tempt the anchoress away from her life of solitary contemplation.

[3] Ancrene Wisse: A Medieval Guide for Anchoresses. Resources on Anchoresses and the Anchoritic Life [online article] Available at: http://faculty.winthrop.edu/kosterj/ENGL512/Handouts/anchoress.htm [Accessed May 2014]

In writings from that period, the anchorite’s body is both imagined and described as synonymous with the anchorhold itself, “an overlap that used spatial language not only to describe the female recluse but also to control her bodily actions” (Gilchrist, R, 2005, p. 10). As this suggests, there were strict rules governing all aspects of Bertken’s life in her cell, from her daily routine to the focus of her thoughts. Many of these rules can be found in the Ancrene Wisse, a thirteenth century guide for anchorites.

One of the purposes of this guide, which was primarily directed at female anchorites, was to teach her how to ‘protect her heart’ [3].

Like all anchorholds of the time, Bertken’s cell would have contained two small windows, one facing onto the street, and one facing into the church, through which she could participate in ecclesiastical services. Though functional, the Ancrene Wisse stresses that these windows were to be feared, as both seeing and being seen contained great potential for evil: “My dear sisters, love your windows as little as you can”. For from sight comes “all the misery that there now is and ever yet was and ever shall be…” (Hermitary,.com, 2003).

Speech was also discouraged, as worldly gossip could tempt the anchoress away from her life of solitary contemplation.

[3] Ancrene Wisse: A Medieval Guide for Anchoresses. Resources on Anchoresses and the Anchoritic Life [online article] Available at: http://faculty.winthrop.edu/kosterj/ENGL512/Handouts/anchoress.htm [Accessed May 2014]

Joanna Peace, 2014

Suster Bertken by Maartje Schalkx, drawing on paper, 2012

Paper collage

Choosing Bertken as the subject of an essay for her museum studies degree, Maartje decided to also draw a comic, to help her, she said, explore the physical side of Bertken’s life, an attempt to inhabit her space. In this section of the larger drawing, you can see that the pencil-drawn panels have become her cell, and the figure of the nun appears small and adrift in the large regular white spaces.

In philosopher Roland Barthes’ series of lectures How to Live Together, he explores the spaces and rhythms of life, solitude and the degree of contact necessary for individuals to create at their own pace. Many of its passages are sparked by his appropriation of Ancient Greek words, and unlocking the metaphorical meaning of the word Anachoresis he says:

“Its foundational act is to break away, the abrupt jolt of departure. This distancing has to be symbolized in some way [and so] Anachoresis = an action, a line, a threshold to be crossed.” (Barthes, R, 1976 – 1977, p. 25)

The physical threshold that Bertken crossed, the stone walls of her cell, no longer exists, as that section of the church was knocked down during the Reformation. What remains is the gesture of drawing that line around her body: a gesture of containment, of protection, of imprisonment, of refuge. All of these and more.

“Its foundational act is to break away, the abrupt jolt of departure. This distancing has to be symbolized in some way [and so] Anachoresis = an action, a line, a threshold to be crossed.” (Barthes, R, 1976 – 1977, p. 25)

The physical threshold that Bertken crossed, the stone walls of her cell, no longer exists, as that section of the church was knocked down during the Reformation. What remains is the gesture of drawing that line around her body: a gesture of containment, of protection, of imprisonment, of refuge. All of these and more.

Photograph of extract from a facsimiles book of Suster Bertken’s writings. Courtesy The Utrecht Archives

Floorplan of the Buurkerk, Utrecht, circa. 15th Century. Found internet image plus collage

Detail of memorial to Suster Bertken, inserted into the pavement at the site where her cell once stood on the Choorstraat, Utrecht

Installation of the video The Chant Went On and On (as he walked along that hot day), 2014

The Utrecht Archive, 2014